The Book of Spies

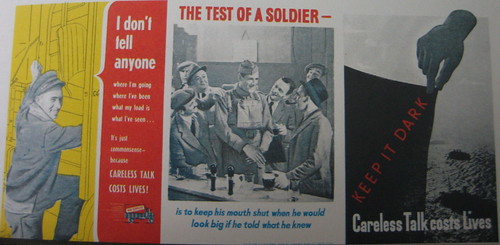

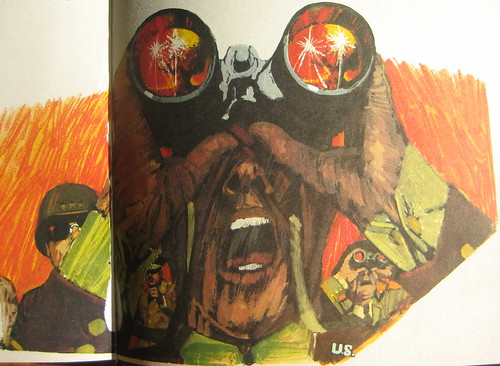

"I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country."Those are the last words of Nathan Hale, possibly the first American spy, seconds before he was hanged by the British in 1776. Hale, a young Yale-educated schoolmaster, was hired by Washington and betrayed by a loyalist relative. The British military official who condemned him to death allowed him to write farewell letters to his mother, sisters, and fiancé, and then tore them up once the noose was put around Hale's neck.Right now I'm reading a wonderful "profusely illustrated" history of espionage, Brian Innes' The Book of Spies, published in 1966. I was reading this book in bed the other night, and (as I tend to do) I fell asleep with the light on. My sister came into my room to turn the light off, and while she was in the room I bolted upright in bed and started...well, 'screaming' isn't the word, they were more like little yelping shrieks. (That wimpy noise was in itself embarrassing--I like to think if there really was an intruder I'd be able to scream properly.) Anyway, I'm pretty sure I was having a dream, a scary dream with spies in it, and for those few seconds before I woke up Kate became part of it.

"I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country."Those are the last words of Nathan Hale, possibly the first American spy, seconds before he was hanged by the British in 1776. Hale, a young Yale-educated schoolmaster, was hired by Washington and betrayed by a loyalist relative. The British military official who condemned him to death allowed him to write farewell letters to his mother, sisters, and fiancé, and then tore them up once the noose was put around Hale's neck.Right now I'm reading a wonderful "profusely illustrated" history of espionage, Brian Innes' The Book of Spies, published in 1966. I was reading this book in bed the other night, and (as I tend to do) I fell asleep with the light on. My sister came into my room to turn the light off, and while she was in the room I bolted upright in bed and started...well, 'screaming' isn't the word, they were more like little yelping shrieks. (That wimpy noise was in itself embarrassing--I like to think if there really was an intruder I'd be able to scream properly.) Anyway, I'm pretty sure I was having a dream, a scary dream with spies in it, and for those few seconds before I woke up Kate became part of it. Scared the bejeezus out of my poor mother!

Scared the bejeezus out of my poor mother!

The Mysterious Stranger

My latest Librivox "read" is Mark Twain's "The Mysterious Stranger." Theodore, the young narrator, lives in a small village in Austria in the 16th century. One afternoon while playing in the woods with a few friends, he meets an attractive young man named Satan (nephew of that Satan--angels have family trees too, apparently), who pulls exotic fruits from his pocket, renders himself invisible, makes little men out of clay and animates them, conjures money out of thin air, and performs lots of other tricks for the boys' amusement. In several conversations over the following months, Satan takes pains to tell Theodore and his friends that humanity, to him and his fellow "angels," is as cosmically significant as fleas on an elephant's back. (If that's so, you'd expect he wouldn't bother associating with these base humans at all, but it's all for the sake of the story, right?) His arrival sparks accusations of theft and witchcraft that leave the claustrophobic community in chaos.Anyway, the following passage totally creeped me out:

"There has never been a just one, never an honorable one--on the part of the instigator of the war. I can see a million years ahead, and this rule will never change in so many as half a dozen instances. The loud little handful--as usual--will shout for the war. The pulpit will--warily and cautiously--object--at first; the great, big, dull bulk of the nation will rub its sleepy eyes and try to make out why there should be a war, and will say, earnestly and indignantly, 'It is unjust and dishonorable, and there is no necessity for it.' Then the handful will shout louder. A few fair men on the other side will argue and reason against the war with speech and pen, and at first will have a hearing and be applauded; but it will not last long; those others will outshout them, and presently the anti-war audiences will thin out and lose popularity. Before long you will see this curious thing: the speakers stoned from the platform, and free speech strangled by hordes of furious men who in their secret hearts are still at one with those stoned speakers--as earlier--but do not dare to say so. And now the whole nation--pulpit and all--will take up the war-cry, and shout itself hoarse, and mob any honest man who ventures to open his mouth; and presently such mouths will cease to open. Next the statesmen will invent cheap lies, putting the blame upon the nation that is attacked, and every man will be glad of those conscience-soothing falsities, and will diligently study them, and refuse to examine any refutations of them; and thus he will by and by convince himself that the war is just, and will thank God for the better sleep he enjoys after this process of grotesque self-deception."

A great writer is often a great prophet as well, no?

Ghosts of Mount Holly

My uncle Dan recently lent me Jan Bastien's Ghosts of Mount Holly, which is the most entertaining book of ghost stories I've read in ages. Mount Holly is the Burlington county seat, a 20-minute drive from where I live in southern New Jersey. Given its rich colonial history, it's not surprising that there are ghost stories attached to the local jail (now a museum, it was designed by Robert Mills, who also designed the Washington Monument), the library (a Georgian mansion), and firehouse (with the oldest continually operating fire company in the country), as well as several restaurants and private homes. There are "Haunted Holly" ghost tours every Friday the 13th, and there's also a Sleepy Holly street party (formerly known as the Witches' Ball) around Halloween-time.The Mount Holly shopping district has undergone a revival in recent years, and a few of these shops are said to be haunted as well. Mill Race Village is a delight--all locally owned stores selling unusual items (stained glass jewelry, quilting supplies, and so forth) in historic buildings. My mom and I have gone shopping here a few times in the last year. One of the most memorable shops is Spirit of Christmas, located in a charming brick house built by Quakers before the Revolutionary War. I've never seen so many Christmas ornaments in all my life (and this is really saying something, considering that my grandmother's collection of snowman effigies easily tops a thousand). It's a sensory overload with all those holiday trimmings crammed into a few smallish ground-floor rooms, so just think how overwhelmed I would have been had I known the building is haunted! Another haunted place is the Robin's Nest, a restaurant and bakery cozily decorated with Victorian paintings and furniture. The food is really good and reasonably priced, and the ghosts usually wait until the place is closed before they start terrorizing the waitresses.True, I love this book partly because I've been to a lot of the places mentioned in it, but it's worth reading even if you have no ties to the area. Many of the stories are seriously spooky, and some are even a bit humorous (like the Hessian soldier who exudes either flatulence or general body odor, the book doesn't specify, and who stomps around in his heavy army boots and tickles the feet of sleeping girls). Actually, one of the creepiest bits of all is the dedication:

My uncle Dan recently lent me Jan Bastien's Ghosts of Mount Holly, which is the most entertaining book of ghost stories I've read in ages. Mount Holly is the Burlington county seat, a 20-minute drive from where I live in southern New Jersey. Given its rich colonial history, it's not surprising that there are ghost stories attached to the local jail (now a museum, it was designed by Robert Mills, who also designed the Washington Monument), the library (a Georgian mansion), and firehouse (with the oldest continually operating fire company in the country), as well as several restaurants and private homes. There are "Haunted Holly" ghost tours every Friday the 13th, and there's also a Sleepy Holly street party (formerly known as the Witches' Ball) around Halloween-time.The Mount Holly shopping district has undergone a revival in recent years, and a few of these shops are said to be haunted as well. Mill Race Village is a delight--all locally owned stores selling unusual items (stained glass jewelry, quilting supplies, and so forth) in historic buildings. My mom and I have gone shopping here a few times in the last year. One of the most memorable shops is Spirit of Christmas, located in a charming brick house built by Quakers before the Revolutionary War. I've never seen so many Christmas ornaments in all my life (and this is really saying something, considering that my grandmother's collection of snowman effigies easily tops a thousand). It's a sensory overload with all those holiday trimmings crammed into a few smallish ground-floor rooms, so just think how overwhelmed I would have been had I known the building is haunted! Another haunted place is the Robin's Nest, a restaurant and bakery cozily decorated with Victorian paintings and furniture. The food is really good and reasonably priced, and the ghosts usually wait until the place is closed before they start terrorizing the waitresses.True, I love this book partly because I've been to a lot of the places mentioned in it, but it's worth reading even if you have no ties to the area. Many of the stories are seriously spooky, and some are even a bit humorous (like the Hessian soldier who exudes either flatulence or general body odor, the book doesn't specify, and who stomps around in his heavy army boots and tickles the feet of sleeping girls). Actually, one of the creepiest bits of all is the dedication:

I hope the author is referring to beloved pets; otherwise that's pretty darn morbid...

Nevil Shute

In European History class in high school, we watched an '80s Australian miniseries called A Town Like Alice, based on the novel by Nevil Shute. It's the story of an English girl caught in Malaya during the Japanese invasion, and who is aided by a courageous Australian soldier during the ensuing death march. I loved the film so much I special-ordered the novel from Waldenbooks, though I never got around to reading it.Ten years later I find myself reading WWII-era novels for secondary research--they're very useful for picking up lingo as well as historical tidbits I might not necessarily find in my nonfiction reading--and I've finally delved into the work of Nevil Shute. He was an aeronautical engineer during the war, and he had a highly successful writing career on the side. (For me that's fascinating enough in itself.) His novels are unsentimental yet very moving. His prose is transparent, and I mean that admiringly. The man knew how to tell a yarn. Reading his work makes me sad for two reasons: 1, that it's hard to find a bestseller these days that's anywhere near as well written; and 2, that Shute isn't more widely read today. It looks like all but his most popular novels are now out of print.There's more than one English-Aussie romance in Shute's body of work--I just finished Requiem for a Wren, and while you can tell what happens from the title it was still a page-turner. (By the way, "wren" is a nickname for a member of the Women's Royal Naval Service.) It's the story of wren Janet, who falls in love with Bill, an Australian "frogman," who's killed during a dangerous mission just before D-Day. After the war Bill's brother Alan (an accomplished RAF pilot who only meets her once) becomes increasingly obsessed with finding Janet again.

That day remained etched sharp in my memory; ten years later I still knew exactly how she moved and spoke and thought about things, so that it gave life to all the knowledge I had gleaned about her from these other people.

Janet pretty clearly suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, and the novel deals with her inability to create a post-war life for herself. She wants very badly to return to naval service because the war had given her a sense of purpose she can't seem to find anywhere else. As Alan (who does the narrating) reflects, "A war can go on killing people for a long time after it's all over." We most often hear the stories of those men and women who survived and built new lives for themselves in the post-war period--because those people, our grandparents and their friends, are still around to tell them--so this novel felt like something of an eye-opener for me.It's also a fascinating look at the life of a trio of service members in the run-up to D-Day. Everyone had their own part to play, but you couldn't talk much about the work you were doing. "Security was so good that neither he nor Bill appreciated the very great importance of the job they had been sent to do." The descriptions of all the tanks and ships amassing for battle is fascinating as well:

At sea, monstrosities of every sort floated in the Solent, long raft-like things proceeding very slowly under their own power, tall spiky things, things like a block of flats afloat upon the startled sea.

Another Shute novel I loved is 1942's Pied Piper, about an elderly Englishman vacationing in the Jura mountains of France who agrees to accompany several small children back to England in the wake of the Nazi invasion. Like Requiem for a Wren (which was published in 1955), the narrative framing device means you know from the get-go that things are going to turn out all right, so it's another testament to Shute's storytelling prowess that you still can't put it down. John Howard, the hero of Pied Piper, is only 69, but Shute portrays him as far more frail than any 69-year-old I've known. He winds up fishing in a remote part of France, intentionally losing touch with the news, because he can't stand sitting around in England feeling impotent. He wants to serve his country in some way, but every application he makes is denied. In Requiem, Janet's 64-year-old father successfully applies for a job as an aircraft identifier in the merchant navy. When Janet remarks on one comrade who looks particularly elderly, her father replies, "He says he's sixty-three. If you don't walk with a stick they don't ask too many questions."And how do children cope with such hideous violence? This is another aspect of war that gets glossed over in the standard history textbooks. John Howard is a tender guardian, doing his best to distract his young charges from the horrors all around them. These kids are so young they don't understand the concept of death yet, so they're very curious. "You mustn't go and look at people when they're dead," he tells them. "They want to be left alone."How did I find these wonderful books if they're out of print? Charlie Byrne's, Galway's best bookshop, has a section of '60s dime-store novels: war, adventure, spies, tear-jerkers, you name it. It's easily overlooked--a narrow bookcase wedged between the Irish literature section and the doorway to the travel/music/film/history room. I've been going to Charlie's for years and I only noticed it a few months ago, on the day I found out we'd sold Petty Magic (so I arrived ready to treat myself). I bought nearly a dozen of these novels for €2-3 each and they've been both entertaining and useful. I love the smell of these old books too.

Thoughts on Anne's 100th

Have you ever found yourself moved by passages in books you've already read multiple times? I've been listening to Anne of the Island on Librivox while knitting, and this paragraph (among others) got me all teary:

Mrs. Rachel Lynde said emphatically after the funeral that Ruby Gillis was the handsomest corpse she ever laid eyes on. Her loveliness, as she lay, white-clad, among the delicate flowers that Anne had placed about her, was remembered and talked of for years in Avonlea. Ruby had always been beautiful; but her beauty had been of the earth, earthy; it had had a certain insolent quality in it, as if it flaunted itself in the beholder's eye; spirit had never shone through it, intellect had never refined it. But death had touched it and consecrated it, bringing out delicate modelings and purity of outline never seen before--doing what life and love and great sorrow and deep womanhood joys might have done for Ruby. Anne, looking down through a mist of tears at her old playfellow, thought she saw the face God had meant Ruby to have, and remembered it so always.

I've lost track of how many times I've read Anne of Green Gables. Looking back on my childhood, I see how crucial the series was in my creative development. In these gloriously sentimental novels, I found a model for my own teenage years—it became important to me to live a "secret life" inside my notebooks and on the canvases I albeit rarely finished. Anne has a lush imaginative life that spills out into the world around her, brightening the lives of everyone she meets.

But as I reread these books as a 27-year-old, I get a certain nagging feeling about Anne's adult choices. There's an Anne appreciation group on Ravelry (all those cozy Victorian cardigans in the films, you know), and someone posted a link to this essay re Anne's 100th anniversary. As Meghan O'Rourke writes, a lot of critics say Anne lets us down when she gives up on a writing career for full-time domesticity, though O'Rourke believes she's still a proto-feminist for all that.

I'm not saying L.M. Montgomery ought to have kept Anne from marrying Gilbert, but why does she have to give up on her writing altogether? In Anne's House of Dreams she spends most of her time baking, sewing, and rejoicing in her pregnancies. There's no mention of Anne sitting down with pen and paper except for letter-writing. There's an opportunity to write the life story of an elderly sailor friend, Captain Jim, but Anne tells herself she isn't up to the task. (A visiting journalist eventually takes on the project, and fame and riches follow the book's publication.)

Meghan O'Rourke writes, "Her physical offspring have to share the house with her fertile imagination." I don't know about that. The last three books in the series focus on the dreams and exploits of her six children, none of whom are anywhere near as interesting as she is. And by the last novel, Rilla of Ingleside, Anne is only ever mentioned in passing.

I suppose the only way to read these later novels is to keep reminding yourself that Anne, like all literature, is a product of her time. As O'Rourke points out, her critics are coming at it with a 21st-century notion of feminine success.

At any rate, it's the first three books I come back to, the stories in which Anne's future is still a bright and shining thing.

Where have all the good husbands gone?

From Anne's House of Dreams, by L.M. Montgomery:

"Don't you know ANY good husbands, Miss Bryant?"

"Oh, yes, lots of them--over yonder," said Miss Cornelia, waving her hand through the open window towards the little graveyard of the church across the harbor.

"But living—going about in the flesh?" persisted Anne.

"Oh, there's a few, just to show that with God all things are possible," acknowledged Miss Cornelia reluctantly. "I don't deny that an odd man here and there, if he's caught young and trained up proper, and if his mother has spanked him well beforehand..."

More on the Anne of Green Gables series in my next post.

The Paper Mammoth

Have you noticed the "Writers' Rooms" link on the right side of the page? I've been daydreaming about a proper study-slash-studio since I was a teenager, and that weekly feature in the Guardian fuels my reveries. I love looking at other writers' workspaces and reading about why they've chosen a particular location, piece of furniture, or wall decoration, and how each element helps (or hinders) them in their work. In my head I've painted the walls and installed (and filled) the bookcases and chosen the upholstery for the wing-backed chair in the corner, scoured junk shops looking for the perfect big old desk, and finally settled upon the perfect filing system. I'm so nerdy I even want to organize my shelves with the Dewey decimal system (um...no...not even kidding).

Of course—seeing as I live in a rented room, do most of my writing at the library, and have books and notes scattered between three separate domiciles—the only part of this fantasy that is currently relevant is the bit about the filing system. I do a lot of talking about "getting organized." You could say that my chaos must be functional enough if I've managed to produce a few publishable manuscripts out of it, but that's not good enough.

It isn't so much a matter of every book, print-out, and notecard being in its proper place as much as having an effective system for filing ideas. I have lots of notes on receipts and torn bits of notepaper, and I do manage to hold on to most of it, but it's all very inefficient. You can just write every random thought down in a notebook, but then each of those individual ideas are eventually going to need sorting according to their respective projects (in a single notebook I could have notes for the project at hand alongside ideas for future novels and stories, notes on a local restaurant I want to write up for the second edition, lists of books to read, and even sketches of sweater designs I'd like to use as inspiration once I have the skillz to knit it). So how to sort it all while keeping it portable?

At first I thought index cards were the best way to go...but then how would I sort and store them? I've tried recipe boxes with tabs, but that seems to work better for sorting ideas within a single project. And if the idea could be expressed in only a word or two, it seemed a little silly to devote a full-sized index card to it. I also started using Stickies as virtual index cards, but then my hard drive crashed and I lost it all. (Incidentally, the Mary Modern folder was the only thing the tech guy was able to retrieve. KISMET!)

Then I had the idea to sort all ideas:

I had asked my dad for a Rolodex a couple Christmases ago, but then I realized I'm too nomadic and didn't know enough people to bother actually using it (and yes, the address book on my iBook dock makes a Rolly pretty much obsolete, but see previous paragraph for why I don't use it much.) I've got tabs for words and phrases, witticisms ("If you had a penis you'd understand" —guess who), witchy business, WWII flashbacks, and so forth, and another tab for everything that isn't Petty Magic. That stuff can be sorted later. So far it's working out pretty well. The only annoying thing is that Rolly cards are actually rather expensive, and I need to find a hard case for when I travel with it.

I know: I'm a total nerd. A pedant, even. Call me what you like, so long as I can keep it all straight.

Mary Modern now out in paperback!

I almost wet myself with excitement the day my editor emailed me the new paperback cover. Isn't it incredible? The über-talented Dan Rembert designed both covers, but he really outdid himself with the re-design. You can't see it too well in the jpeg, but those faint horizontal lines are DNA code. Captures the quirky spirit of the book just perfectly.At the back of the book you'll find a reading group guide as well as an author essay written especially for the paperback edition. I wrote about how my great-grandparents' engagement portrait sparked the idea.Hard to believe it's been a year since the novel came out. I'm trying not to think about how well the paperback will end up selling, and actually, it isn't all that hard when my head is so full of plot lines and bits of dialogue from Petty Magic...

I almost wet myself with excitement the day my editor emailed me the new paperback cover. Isn't it incredible? The über-talented Dan Rembert designed both covers, but he really outdid himself with the re-design. You can't see it too well in the jpeg, but those faint horizontal lines are DNA code. Captures the quirky spirit of the book just perfectly.At the back of the book you'll find a reading group guide as well as an author essay written especially for the paperback edition. I wrote about how my great-grandparents' engagement portrait sparked the idea.Hard to believe it's been a year since the novel came out. I'm trying not to think about how well the paperback will end up selling, and actually, it isn't all that hard when my head is so full of plot lines and bits of dialogue from Petty Magic...

Thoughts on Criticism and Rejection

Rejection is hard. It gets a little easier as you go on, but not by much. The sooner you start to devise little coping strategies to keep your ego patched, the better off you'll be.Whenever I got to feeling down over a rejection (or, later on, a snarky Amazon review), I thought: Well, the person who is criticizing me [an editor, reviewer, or random reader] can't do what I'm doing--they don't have the guts, or the talent, or either of the two. This may sound snarky in its own right, and maybe it is. It also isn't fair to all those wonderfully talented editors and agents out there, those midwives and shepherds of the literary world. Then again, I've found that the most talented editors and agents in the business do not write rejection letters that leave you feeling like a sack of elephant crap. Those are the letters--tactful, and sometimes even very encouraging--that spur you on.This attitude I'm talking about--THEY can't do it and therefore I should take their criticism with a grain of salt--is merely a coping strategy. I'm not talking about the criticism that you know in your heart is wise and right on the money. This is just something to keep in mind when you start feeling like you've seriously overestimated your own talent. Even if you've written the sloppiest, most derivative novel ever put to paper, a manuscript that will never see publication, you've still accomplished more than most folks ever do.I'm not discounting the job of reviewers. Literary criticism is as necessary as literature itself, and can be every bit as enjoyable to read. It just drives me nuts when I read a snarky review. It's like when a reviewer takes pains to include some line about Mary Modern not holding a candle to the original Frankenstein. First of all, it's NOT Frankenstein, nor is it a retelling. Nobody was claiming on the dust jacket or marketing materials that I wrote an instant classic. It comes off sounding like a jab, and it's completely unnecessary. In another case, a reviewer dismissed my characters as ciphers--never mind that I can tell you every character in that book is based on a person (or, more often, a series of people) I've known in real life. As I read that particular review, it was abundantly clear that the reviewer had decided not to like my book before he even cracked the spine.You definitely start to sense a bit of envy between the lines of these reviews sometimes. Perhaps the reviewer is himself a frustrated fiction writer, so he says your work is derivative, mediocre, or what have you. Mind you, I'm not whining or being underhandedly smug here--I'm saying this because I often felt this impulse myself before I was published. I have taken notice of several literary catfights in recent years, most memorably between Laura Miller of Salon.com and the novelist Chuck Palahniuk. She wrote a review of Diary in 2003 that was so unbelievably negative it was downright undignified, and he responded with a letter to the editor that had me jumping with glee:I have never responded to a review, perhaps because I've never gotten such a cruel and mean-spirited one. Please send me a copy of your latest book. I'd love to read it.Until you can create something that captivates people, I'd invite you to just shut up. It's easy to attack and destroy an act of creation. It's a lot more difficult to perform one. I'd also invite you to read the reviews Fitzgerald got for "Gatsby" from dull, sad, bitter people -- like yourself.Amen, Chuck.(By the way, I haven't read any of Mr. Palahniuk's novels, but I don't care if Diary was the worst piece of tripe published in this or any other century; nothing could justify the writing of probably the nastiest, snarkiest piece of "journalism" I have ever read. Even this Salon critic's less controversial columns have really annoyed me from time to time--like when she dismissed David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas--which is an utterly sublime novel--as an albeit-fun pastiche. She's sounding more and more like a frustrated novelist, eh?)Anyway, the upshot of all this is that one must read a book review with a critical eye. Sometimes reviewers are needlessly harsh for reasons that have more to do with them than the author, and sometimes there are good reviews of mediocre books written by acolytes. Sometimes there are reviews of books by great writers that are criticized by novelists whose work is patently inferior, or a novelist who is insecure about her own place in the literary canon and acts on an urge to cut down a fellow author. And sometimes, once in a blue moon it seems, there's a thoughtful review written by someone with no angle at all.But that's not the real reason I've stopped reading book reviews. The real reason is that avoiding them is another coping strategy for me--otherwise I'd be reading glowing reviews of books with rehashed plots thinking, Damn it, why did this newspaper ignore my book? Also, I stopped reading the Amazon/Librarything/whatever reviews not too long after Mary Modern was published. There are some really ridiculous ones out there--there's at least one two-star review that spells my name "Deangeiiis," and says my book was poorly edited without even bothering to make a logical case for the assertion. WHO takes these people seriously? Who? Not me, that's who--those crappy, illogical, useless reviews can only raise my blood pressure.

More stuff to spook you

While I was writing Mary Modern I often took breaks in the middle of the night to read the supposedly true ghost stories at Castle of Spirits. This scary-story habit definitely flavored my fiction. I thought I'd post links to a couple of my very favorite stories, "Happy Birthday, Mr. Poe," "A Voice in the Attic," and "A Song for Clara." "A Voice in the Attic" freaked the crap out of me, so consider yourself warned.Another story that made a profound impression on me is Le Fanu's "Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter" (you can also listen to it at Librivox, but unfortunately the sound quality is poor). Schalken was a real-life artist in the 17th century, whose eerie portraits of girls in candlelight inspired this tale of a poor young artist's apprentice struggling to free his beloved from the greedy grip of a very rich, very frightening old man.There are other good stories in the Librivox Ghost Story Collection #1 (click same link above), particularly E. Nesbit's "Man-Size in Marble" and "Uncle Abraham's Romance." Edith Nesbit is best known for her children's fiction--thanks to Ailbhe for giving me a copy of The Enchanted Castle!--but I'm finding her ghost stories even more enjoyable. I've got to pick up a copy of The Power of Darkness, a new collection of the same stories originally published as Grim Tales in 1893.One last note: before you wonder if any of this is appropriate bedtime reading, I'd just like to mention that I finally read Flannery O'Connor's "A Good Man is Hard to Find" the other night. I can see why she's considered one of the 20th-century masters of the short story, but damn, was it ever disturbing. I had to read a few more ghost stories on Castle of Spirits just to try to clear my head.

Cúirt, finally

Cúirt (roughly pronounced "corch") is Galway's international literary festival. It's a really exciting time to be here. Sometimes there are famous authors you can't wait to see and sometimes you discover the work of a new writer, and even if you don't attend a single reading there's still lots of craic to be had at the pub afterwards. It is very much a literary festival though--hugely 'prestigious' to the point where the festival committee won't ask any writer who's garnered 'too much' commercial success. Some folks are pretentious (more the hobnobbers than the writers themselves), but the rest of us feel free to make fun of them.This year the speaker I was most excited about was Samantha Power, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and former foreign policy adviser to Barack Obama. I couldn't believe tickets for this event were only €6! And let me tell you, she is AMAZING. Not only is she incredibly smart and articulate--you'd expect that from a Pulitzer winner, right?--but she is also unbelievably humble. Everything she said impressed me. She read a short excerpt from her new book, Chasing the Flame, but she spent most of the hour beforehand giving us clear and thorough background information without aid of a single notecard.There was a Q&A afterwards and naturally people asked plenty of asinine questions, all of which she answered with grace and humor. One guy asked, "If Obama is elected, how long do you think it will be before there's an attempt made on his life?" There was a general hmmph of disdain from the rest of the theater as Ms. Power answered (paraphrasing here), "The concise answer to that is, I don't know."As for the Pulitzer, she very candidly told one audience member that she believes the reason she won is that the judges probably felt like they were "doing something" positive just by giving the award and thus raising people's awareness that genocide is still happening. A Problem from Hell was rejected by something like twenty-two publishers.I have a copy of A Problem from Hell, but I probably wouldn't have asked her to sign it even if I had brought it with me. Whenever I meet an author, even if it's an author I haven't read yet (and thus, haven't had the chance to become speechless with awe over), I always manage to say something stupid. (This goes for musicians, too, which is part of why I didn't stick around after the Elbow show even though I'd brought one of their CDs with me.) I've gotten to the point where I'd rather just avoid any opportunity to put my foot in my mouth.Galway is a great city for festivals in general--the Arts festival program is being launched tonight. Loads of plays, concerts, and art the last two weeks of July!

Another audio treat: The Canterville Ghost by Oscar Wilde

I remember seeing a TV movie version of "The Canterville Ghost" starring George C. Scott in the '80s, but it's taken me this long to read Wilde's original short story, a delightful gothic satire. Sir Simon de Canterville murdered his wife in 1575, and since his own mysterious demise he has taken great relish in terrorizing his descendants at Canterville Chase. Finally fed up, the last lord of Canterville sells the estate to a pragmatic American minister and his family, none of whom are the least bit frightened by the ghost's theatrics.

With the enthusiastic egotism of the true artist, he went over his most celebrated performances, and smiled bitterly to himself as he recalled to mind his last appearance as "Red Reuben, or the Strangled Babe," his début as "Guant Gibeon, the Blood-sucker of Bexley Moor," and the furore he had excited one lovely June evening by merely playing ninepins with his own bones upon the lawn-tennis ground...

Listen on Librivox or read it at Project Gutenberg.

The Mortal Immortal

This evening I stumbled upon a delicious short story by Mary Shelley called "The Mortal Immortal." I listened to the Librivox recording (read by David Barnes, who has a very soothing English accent) while knitting.

Mary Modern has an obvious debt to Frankenstein, and yet I'm unfamiliar with any of her other works. Her personal life fascinates me though--I've heard much about her writing Frankenstein at a very young age (18?) as part of a scary-story competition during a house party (if one could call it that) in some great gloomy castle with Shelley and a few of their friends, and about how Shelley left his wife for her and wife #1 had to commit suicide before they could marry (though they already had a couple kids together by that time); but the story that really intrigues me has to do with the young Mary bringing her books to the graveyard to study at the grave of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, and how she and Percy Shelley had their illicit meetings there. It really sounds like Mary Shelley not only wrote gothic stories--she lived one as well.

Anyway, read or listen to "The Mortal Immortal." It's wonderful.

A little fish meets a Big Fish

[Haven't forgotten to write about Cúirt. Next time!]I want to tell you a really cool story that begins more than four years ago now. My father handed me the USA Today books section and pointed to this article about novelist Daniel Wallace and Big Fish. In the interview, Mr. Wallace expresses amazement at the eventual runaway success of his novel, and talks about how much he enjoyed his cameo in Tim Burton's big screen adaptation. I had seen the film with my father and we both enjoyed it very much.But the real reason he pointed me to the article was this: Mr. Wallace told the interviewer he had written five novels before Big Fish, all of which had been rejected by publishers. At the time, my Practice Novel was generating quite a high stack of rejection letters and I was feeling depressed about it. My dad told me to take heart, that perseverance would eventually bring success, and this article was proof of it. At first I thought, "I think I can write one more novel, and if that novel is rejected, then I'm at the end of my rope." Then I thought, "If Daniel Wallace can write five novels and break out with the sixth, then maybe I can too." Anyway, I stuck with it, and Novel #2 turned out pretty well for me (tee hee). When I gave advice to other writers, I always emphasized perseverance--precisely because of this USA Today article and Daniel Wallace's story.Fast forward to October 2007. I'd published Mary Modern a few months back and now I was on my way to the Midwest Literary Festival, my first ever (and let me tell you, I was so excited). Daniel Wallace was also attending, though I didn't expect I'd get the opportunity to thank him for his inspiration. I'd be too intimidated, anyway. Well, I actually did meet Daniel Wallace in the backseat of a van on our way to the authors' welcome barbecue, but I, ever-clueless, had it in my head that this guy whose hand I'd just shaken was a literary agent (in fairness, he was only introduced to me as "Dan"). Anyway, I eventually realized who he was, and wondered if I'd be able to talk to him, though I was still feeling a little intimidated. (There were so many established writers at this festival that it was hard not to feel a little mouse-like at first, though I quickly relaxed when I realized just how nice and down-to-earth they all were.)On the last day of the festival, they had scheduled me for a panel discussion that was going to end right around the time I needed to be taking a car back to the airport. I booked it out of the conference center and down a few blocks back to the hotel to pick up my bags. When I got there, I saw the appointed Lincoln town car, and then I saw Daniel Wallace right beside it. We were going to be sharing a ride to the airport! I couldn't believe the serendipity of it.As I loaded my bags he said something to the effect of, Are we going to have a chat? I'd like to have a chat but if you'd rather not I just want to know in advance. SO NICE! Of course I want to have a chat, I said. So on the way to the airport I told him the story I've just told you, about how much that USA Today article meant to me. He actually seemed rather taken aback--he is just such a genuinely humble guy. I said, "If my dad had pointed to that article and said, 'Three and a half years from now you'll be riding in the backseat of a Lincoln town car with Daniel Wallace, talking about your publishers and teaching creative writing classes,' I would never have believed him."So that's my little story of how perseverance pays off.

[Haven't forgotten to write about Cúirt. Next time!]I want to tell you a really cool story that begins more than four years ago now. My father handed me the USA Today books section and pointed to this article about novelist Daniel Wallace and Big Fish. In the interview, Mr. Wallace expresses amazement at the eventual runaway success of his novel, and talks about how much he enjoyed his cameo in Tim Burton's big screen adaptation. I had seen the film with my father and we both enjoyed it very much.But the real reason he pointed me to the article was this: Mr. Wallace told the interviewer he had written five novels before Big Fish, all of which had been rejected by publishers. At the time, my Practice Novel was generating quite a high stack of rejection letters and I was feeling depressed about it. My dad told me to take heart, that perseverance would eventually bring success, and this article was proof of it. At first I thought, "I think I can write one more novel, and if that novel is rejected, then I'm at the end of my rope." Then I thought, "If Daniel Wallace can write five novels and break out with the sixth, then maybe I can too." Anyway, I stuck with it, and Novel #2 turned out pretty well for me (tee hee). When I gave advice to other writers, I always emphasized perseverance--precisely because of this USA Today article and Daniel Wallace's story.Fast forward to October 2007. I'd published Mary Modern a few months back and now I was on my way to the Midwest Literary Festival, my first ever (and let me tell you, I was so excited). Daniel Wallace was also attending, though I didn't expect I'd get the opportunity to thank him for his inspiration. I'd be too intimidated, anyway. Well, I actually did meet Daniel Wallace in the backseat of a van on our way to the authors' welcome barbecue, but I, ever-clueless, had it in my head that this guy whose hand I'd just shaken was a literary agent (in fairness, he was only introduced to me as "Dan"). Anyway, I eventually realized who he was, and wondered if I'd be able to talk to him, though I was still feeling a little intimidated. (There were so many established writers at this festival that it was hard not to feel a little mouse-like at first, though I quickly relaxed when I realized just how nice and down-to-earth they all were.)On the last day of the festival, they had scheduled me for a panel discussion that was going to end right around the time I needed to be taking a car back to the airport. I booked it out of the conference center and down a few blocks back to the hotel to pick up my bags. When I got there, I saw the appointed Lincoln town car, and then I saw Daniel Wallace right beside it. We were going to be sharing a ride to the airport! I couldn't believe the serendipity of it.As I loaded my bags he said something to the effect of, Are we going to have a chat? I'd like to have a chat but if you'd rather not I just want to know in advance. SO NICE! Of course I want to have a chat, I said. So on the way to the airport I told him the story I've just told you, about how much that USA Today article meant to me. He actually seemed rather taken aback--he is just such a genuinely humble guy. I said, "If my dad had pointed to that article and said, 'Three and a half years from now you'll be riding in the backseat of a Lincoln town car with Daniel Wallace, talking about your publishers and teaching creative writing classes,' I would never have believed him."So that's my little story of how perseverance pays off.

More on travel-writing (this is a long one)

This morning my sister pointed me to a very interesting feature article on a confessional memoir by a Lonely Planet researcher called Do Travel Writers Go to Hell? People are asking questions about how thoroughly (and ethically) the guidebooks they use are actually researched, and rightly so. Apparently this writer accepted lots of freebies and engaged in plenty of drugs and sex along the way, and while it's safe to say most guidebook writers are far more responsible than this guy was, there is a great deal of truth in some of the things he's saying. This, for example (from the WaPo article, not the memoir itself), is 100% true:[Kohnstamm] says he's being criticized because he revealed guidebooks' dirty little secret: Authors can't get to every place they're expected to review because publishers don't give them enough time or money to do the job properly. So, he says, he was forced to do a "mosaic job," relying in some cases on information from local contacts, fellow travelers and the Internet.Even the most responsible guidebook writer has to resort to these tactics. I worked really hard on Moon Ireland, but I still had to rely on secondhand information far more often than I was comfortable with. I'll elaborate.First of all, here's the number 1 rule of guidebook-writing: don't expect to make any money. You will subsist and that is all. Number 2: taking freebies is unacceptable. I had to accept comps everywhere I went while I was researching Hanging Out in Ireland back in college, because they gave us all of $3500 to research half the country (originally the fee was going to be $2500, but my co-writer held out for more money. Thank goodness for Tom, who was older than I was and far more sensible). My editors encouraged us to accept freebies because otherwise we'd run out of money after two weeks and we were there for five to seven (only five, in my case--can you imagine covering half of Ireland in five weeks? They told me I'd have to do some fudging. Yes, my own editors told me to cut corners.) This was a shoestring guide on a shoestring budget.Even putting that question of ethics aside, accepting a free meal, room, or tour will not give you an accurate idea of the level of service a typical tourist will receive. You don't want to say "yeah, this place is great!", when the owner is actually not a nice person at all, but was only kissing your butt because you're a guidebook writer.How do I know this? I've admitted I accepted freebies from hostels and restaurants every place I went for Hanging Out, but that's not how I know. In May 2006 I visited--or attempted to visit--a very upscale B&B (with its own gardens open to the public) off the Ring of Kerry, and was shooed away by the owner, who is hands down the meanest person I have ever encountered in Ireland (though incidentally, she is not Irish). There had been a storm the night before, and the garden was closed because of damages. There was a huge sign saying so, but the gate to the house was open. I drove through the gate and was met on the road by this nasty woman, who demanded I get off her property even when I tried to explain that I was writing for a guidebook and was interested in the B&B. I don't think she even heard what I was saying, she just kept snarling that the B&B was fully booked and to get out immediately. Let me impress upon you (as if I haven't already): this woman's behavior was HORRIBLE and I would discourage anyone from staying at that B&B no matter how luxurious it might be. So imagine my disgust when I opened Lucinda O'Sullivan's guide to Irish B&Bs and noticed she'd written about just how lovely and kind the proprietor is. Someday I'm going to write Lucinda O'Sullivan and tell her how disappointed I am in her book. (If anyone is interested in knowing which B&B I am talking about, please feel free to email me. I just don't want to mention it by name and get a pile of angry emails over it.)Out of necessity, I was doing much of my research during low season, when many B&Bs and restaurants were closed, only open weekends, or whatever. Say I stopped on a weekday night in February at a certain B&B, and the proprietor heartily recommended a restaurant in town. I got to the restaurant and found it was only open on weekends until after Easter. So instead, I had pub grub for dinner--adequate, nothing to write home about--and both the pub ('steaks, seafood, and paninis, gets the job done') and the restaurant ('run by an Irishman and his French wife, Continental cuisine, much loved by locals') would get write-ups. Other times I could only budget one night in a certain town, but I might need to write up five accommodations. How could I possibly do this without spending five nights in this town? I couldn't, of course. I might just stop by and have a chat with the proprietor (which would usually turn into a two-hour gab because the lady would be very eager to impress me, so I didn't do this too often because it would eat into my sightseeing time too much--see, I couldn't stop by and ask to take a look around without telling them I was writing a guidebook); or, more often, I might hear of a good B&B from other travelers, or other guidebooks, or Trip Advisor, and do as much internet research as I could to be reasonably certain the accommodation was worth recommending. Then I pledged to visit the place and stay there myself for the second edition. That was the absolute best I could do under the time and financial constraints. I'm not happy about it, but at least I know that, since I'm the sole author of Moon Ireland, I can make sure all the info in the new edition is gathered firsthand. I'm going to go through the whole book before the revision process starts and highlight every pub, restaurant, and B&B I need to visit, and then I'm going to do it. This is a big part of why I think the Moon guides are so great--they're written by only one person, or a team of two, and I believe that higher level of personal responsibility ultimately leads to a more reliable guidebook. Lonely Planet is generally my go-to guide for other locations, but it does bug me sometimes that they don't delete/update write-ups of accommodations and restaurants that have closed (or moved to another location) years ago.According to this WaPo article, Moon researchers get above-average advances, and I believe it. Even though I lost money doing this guidebook (for Ireland is the second-most expensive country in Europe), I couldn't have reasonably expected any more than they gave me--after all, guidebooks have an awfully short shelf life. Mine has been out one year, and already I've found several restaurants that have closed in Galway City alone. It's not an old guidebook, but it's already out of date (come to think of it, these books are out of date even before they're published). When I'm in the travel section at Borders looking to plan my next vacation, I always look at the pub dates on the guidebooks I have to choose from. If I were a tourist looking for an Ireland guidebook, I might pick up a 2008 edition of some other guidebook instead of Moon Ireland. (Even so, the 2008 guidebooks are the product of research done in 2006 or early 2007.) What I'm trying to say is, I don't even think I'm going to earn out on the advance Avalon gave me. The pay is tight because the operation doesn't float if they pay you a liveable wage.Tourists should keep all this in mind. But know this: we travel writers may not be perfect, but we're travelers just like you, so we understand how important a reliable guidebook is in making your vacation a happy one.

Thoughts on the Creative Cycle

Until recently my website bio concluded with the following line:At the moment Camille is working on a new novel that will feature chocolatiers, burlesque dancers, antiques dealers, pyromaniacs, and a runaway snow globe, though not necessarily in that order.Tongue-in-cheek, but only to a point. At the time I wrote that I was doing a lot of random reading and wasn't quite sure what I wanted to write about. Since this is novel #3 for me, I have enough of a work history now to notice a pattern of peaks and troughs in my creativity. I have never finished revising one novel and started writing the new one the following week or month (and I've always wondered about those writers who say they do). In between revising the Practice Novel and beginning Mary Modern there were a good seven or eight months of trying to develop various ideas that ultimately weren't viable, at least in the form I gave them at the time. The Mary Modern-Petty Magic interim period was a good deal longer--partly because I was working on Moon Ireland, but more because I was putting a fair amount of pressure on myself to come up with something that would top Mary Modern. All in all, it was roughly a year between finishing up the guidebook and MM edits and beginning Petty Magic.Even with Mary Modern promotional stuff taken into consideration, 2007 didn't feel like a productive year for me, although I figured even at the time that "trough" was a necessary part of the cycle. All the false starts eventually lead you closer to what you're meant to be working on. In 2007, these false starts took the form of seventy pages of a novel I later realized I could have written five or six years ago (fortunately I could cannibalize the strongest parts, and for two different projects), and the start of another more promising novel that clearly needed more time to simmer. I also wrote a few short stories I will revise at some stage. (As my friend Danny put it: stories, like jelly, need some time to set.)So there seems to be a pattern of filling up (reading eclectically and voraciously; collecting random bits of dialogue/character quirks/fun words/plot jumping-off-points on little scraps of paper - though these bits will eventually work their way into many future stories, not just this one coming up), formulating an idea, writing up a storm, then another eclectic reading and gathering period that well outlasts the novel revisions. (I've read that this cycle is personified by a trinity of Hindu gods: Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer.)It's that filling-up period that has all the false starts in it. You're trying to write before you know what you actually want (or need, or should) write about. And you know you're in the formulation stage when you start to notice little serendipities: books of particular relevance seem to pop off the shelf, and you may notice subtle links between two seemingly unrelated topics that have both intrigued you lately. There is a definite sense of things falling into place, and a lovely tingling excitement whenever you think of your new Big Idea.That, and relief that you aren't faking it.

Tom's Midnight Garden

Philippa Pearce published this delightful award-winning English fantasy novel in 1958, and it is a must for any child's bookshelf. It seems like the novel isn't nearly as well known in America.Tom's brother is stricken with the measles, so Tom must spend his summer holidays in a "poky old flat" with his childless aunt and uncle. The flat is a small part of what was once a grand house, but all that remains of its former stateliness is the grandfather clock in the front hall; out the back door are nothing but trash bins and concrete driveways. When the clock strikes thirteen on Tom's first night there, he comes downstairs to investigate, and when he opens the back door he finds a glorious garden with plenty of opportunities for play (Tom is under quarantine, so his indoor daytime existence is stultifying). He forms a lasting bond of friendship with a girl he meets in the garden—the only one of the house and garden's inhabitants who can see him. In rereading this novel I thought more than once of The Time Traveler's Wife:

Philippa Pearce published this delightful award-winning English fantasy novel in 1958, and it is a must for any child's bookshelf. It seems like the novel isn't nearly as well known in America.Tom's brother is stricken with the measles, so Tom must spend his summer holidays in a "poky old flat" with his childless aunt and uncle. The flat is a small part of what was once a grand house, but all that remains of its former stateliness is the grandfather clock in the front hall; out the back door are nothing but trash bins and concrete driveways. When the clock strikes thirteen on Tom's first night there, he comes downstairs to investigate, and when he opens the back door he finds a glorious garden with plenty of opportunities for play (Tom is under quarantine, so his indoor daytime existence is stultifying). He forms a lasting bond of friendship with a girl he meets in the garden—the only one of the house and garden's inhabitants who can see him. In rereading this novel I thought more than once of The Time Traveler's Wife:

This was Hatty, exactly the Hatty he knew already, and yet quite a different Hatty, because she was—yes, that was it—a younger Hatty: a very young, forlorn little Hatty whose father and mother had only just died and whose home was, therefore, gone...

He never saw the little Hatty again. He saw the other, older Hatty, as usual, on his next visit to the garden. Neither then nor ever after did he tease her with questions about her parents. When, sometimes, Hatty remembered to stand upon her dignity and act again the old romance of her being a royal exile and prisoner, he did not contradict her.

Months and even years go by between Hatty's seeing Tom in the garden, though he goes there and plays with her every night. And when he gets back to his room in his aunt and uncle's flat after hours of playing in the garden with Hatty, the clock reads just a few minutes past midnight.I first read Tom's Midnight Garden when I was nine or ten years old, and because it was a school copy I couldn't just pull it off the shelf years later when I was wondering about the title and author of that great children's novel I'd read back in Challenge Literature (which was this special once-a-week class for kids with high scores on the standardized tests, or however else they measured our potential. There were four Challenge classes: Math, Literature, Art, and Music. It sounds nerdy, but the Challenge classes were my favorite part of elementary school.) Ailbhe recently mentioned Tom's Midnight Garden over dinner, and I got really excited because I knew it was the same book I'd been searching for on the internet. I got an old library copy via Amazon Marketplace and I've enjoyed it as much as I did when I was nine. Even got a bit teary at the end.Hooray for secondhand books! I like the idea of a book arriving with a history already. This paperback copy is stamped MERRICK LIBRARY, and it has that wonderful musty smell of old paper. On the back cover I see:

DATE DUE:SEP 12 1981JAN 27 1982

And at the bottom:

2¢ PER DAY OVERDUE FINES.OVERDUE NOTICES WILL NOT BE SENT ON THIS PAPERBACK.

I wonder if the second person who took it out never returned it.

I heart Angela Carter

I am rationing the oeuvre of the great Angela Carter. I always wind up closing her books, sometimes mid-paragraph, shaking my head and getting a little teary-eyed to think that there will be no more of her novels or short stories. Right now I'm reading another story collection of hers, Saints and Strangers (originally published as Black Venus in the UK), and this passage from "The Kitchen Child" is just too lovely not to share:

I am rationing the oeuvre of the great Angela Carter. I always wind up closing her books, sometimes mid-paragraph, shaking my head and getting a little teary-eyed to think that there will be no more of her novels or short stories. Right now I'm reading another story collection of hers, Saints and Strangers (originally published as Black Venus in the UK), and this passage from "The Kitchen Child" is just too lovely not to share:

And, indeed, is there not something holy about a great kitchen? Those vaults of soot-darkened stone far above me, where the hams and strings of onions and bunches of dried herbs dangle, looking somewhat like the regimental banners that unfurl above the aisles of old churches. The cool, echoing flags scrubbed spotless twice a day by votive persons on their knees. The scoured gleam of row upon row of metal vessels dangling from hooks or reposing on their shelves till needed with the air of so many chalices waiting for the celebration of the sacrament of food. And the range like an altar, yes, an altar, before which my mother bowed in perpetual homage, a fringe of sweat upon her upper lip and fire glowing in her cheeks.

Gorgeous.

Post #3 weeeeeeeeeeeeee!

I do sometimes worry about offending people though. The character I am channeling right now is bawdy and outspoken, and behaves in ways I would absolutely never. I make a brief foray into the so-called decadence of 1920s Berlin, and so my character refers to "sipping pink champagne with kohl-eyed nancies." Politically incorrect epithet aside, my stepsister's name is Nancy. Will she be offended?, I wondered as I wrote that line. I have a line about a town called Harveysville and how it sounds like "a hamletful of inbreds." There may be dozens of Harveysvilles across the country. If any of their inhabitants pick up this novel, will they be offended? I think about things like this as I write--along with the inescapable squirminess of making sexual references knowing my grandparents are someday going to read it--but in the end I know I have to ignore these worries or the story's integrity will suffer. That might sound a little pretentious, but what's the point in writing this character's story if I'm going to censor it? The new novel is written in the first person, and when a story is written in the first person you'll inevitably have some readers who think your beliefs are synonymous with your character's. Heck, they'll think so even if you write in the third person.While we're on the subject of offending people, I might as well note that it seems I have offended a few Republicans who didn't like the fact that one of the main characters in Mary Modern is a scientist who is vehemently anti-Bush. (She's from a clan of Massachusetts Catholics, so it's no real shocker, is it?) My editor and I did discuss toning down the liberal rhetoric in the novel, but ultimately I decided to follow my own character's advice: "Life is too short for subtlety." I noticed a review on Amazon that said this lack of subtlety "took the shine off a bit" from an otherwise fine novel, and that criticism is perfectly valid. But when people say my novel is "bad" just because they don't agree with my characters' political beliefs, well...that seems rather ignorant.So I'm not going to worry about offending people--or at least I'll try not to!

The "Amy Tan Vow of Silence"

When my friend Kate T. and I were in college and just beginning to write, we told ourselves we would subscribe to the "Amy Tan Vow of Silence." Kate had come across an interview in which Ms. Tan stated she never discussed anything she was working on until it was finished.

When one is just starting to write seriously, I think this attitude is crucial. It is not the time to be getting advice from your friends or family whether you've asked for it or not, and it's not the time to be hearing people say "I don't know, that sounds kind of silly. Why don't you write about X instead?" The only opinions you should be paying any attention to are those of your characters.

At some point you will meet a kindred spirit, hopefully more than one, whom you can trust to be both encouraging and tactfully and constructively critical. I found that I could unzip my lips once I'd met a few people who fell into that category in my M.A. program. My friend Ailbhe's comments and questions about the plot of Mary Modern proved really useful, and her enthusiasm got me even more excited about what I was working on. And of course, if I hadn't initially run the premise by Kelly I might never have written it in the first place (I was afraid it might be too weird or ridiculous to develop any further, but she told me to go for it). It was the same deal this time around: I had an idea I was excited about, but I also had a few reservations, but when I told Ailbhe about it she encouraged me to put aside my hang-ups and get on with writing it.

But in the very beginning I think it's better to button your lip. Until the thing has taken a definite shape in your head and you've gotten a good chunk of pages down, and until you've found a true-blue writing partner, I think a vow of silence is the way to go. Tactfully decline to respond to any questions you just don't feel like answering, and don't worry about offending people.

At this point, I have no qualms about telling my close friends what I'm working on, but it's when people I meet in passing ask me about the plot of my new novel, what it's called, and how I'm categorizing it, that I tend to freeze up. All I tell them is that it's literary fiction-slash-fantasy, like Mary Modern without the faux-science. I don't even tell people what it's called. For some reason I'd rather wait until I know when it's going to be published to circulate the title. Another consideration is that if I haven't yet told my mother, my agent, or my editor what it's called, I'm sure as heck not going to tell someone I barely know. Having said this, I'm certainly happy when people care enough to ask.