The Pace of Nature

On a recent trip to San Francisco I reconnected with Maura McElhone, a friend from Galway and fellow graduate of the M.A. in Writing program at NUIG. A native of Derry, Maura now lives in Northern California. She says, "I firmly believe that life isn't so much about where we are or how we live, and all about who we're with as we live it. I dream of publishing a book, and of that book making an impact on someone, somewhere in the world." When she told me about making a set of extraordinary friends on four legs, I asked if she'd write a guest post for me. I hope you enjoy this story as much as I did.

***

Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.

—Emerson

It’s a chilly enough evening here in the north San Francisco Bay Area, but I've left the living room window open. I need to keep a constant ear out for them, you see: the deer that come by most nights now for a quick snack, and, in the case of one very special animal, the odd head rub, too.

I first met the deer I’ve come to know as “Gimpy” a little over a year ago when he, along with his mother (easily distinguishable by the sizable notch in her right ear and named “Mango” after the sweet yellow fruit that was the first thing she ate from my hand), would stop to graze on the grassy hillside just beyond my apartment during the spring and summer months.

Once the temperature dropped and winter came, the deer disappeared. To where, exactly, I don’t know. The fantasist in me likes to think of them kicking back with a cocktail on the deer equivalent of Barbados while waiting out the colder months.

When they returned in May of this year, I immediately noticed that the baby was having difficulty walking. It was only when the animals came closer that I was able to see the white bone protruding from his right hind leg. The break was clean, but this offered little consolation as I watched the tiny Bambi-like creature hobble around, dragging the useless limb behind him.

I began ringing various animal rescue centres, but at 9pm, only the answering machines were picking up. Finally, I got through to a woman in Virginia who ran a deer rehabilitation centre. She advised me not to ring the local humane society, but rather, to “let nature do its thing.” Breaks like this are common in young fawns, apparently, and if the animal is at all mobile, and its mother is still with it, it stands a good chance of recovery. The best thing I could do, she told me, was to give him food and water: let him come to associate that grassy hillside as being a safe haven, a place he could come for sanctuary or help. “If he needs you,” she said, “he’ll find a way to let you know.”

Looking at it on paper now, it does seem slightly ridiculous: the idea of this wild animal going out of its way to seek help from a human, a creature they fear from birth. At the time, however, I didn’t linger on the logistics. All I knew was that as long as this little animal continued to find his way to my apartment, I would do everything I could to care for him. I knew it would be tough. I was a human seeking to make a difference in a world that wasn’t mine, after all. The only way this would work would be if somehow deer and human could meet halfway.

So I interfered as little as possible. When Mango and the fawn I’d taken to calling “Gimpy” came by, I’d feed them and during the particularly hot days this summer, I left out a basin of water from which they drank readily. There was a period of maybe two months when I didn’t see either deer, and while I worried, I had to trust that as long as nature was in charge, things would play out as they were meant to.

As it turned out, he’d managed just fine. When he returned with Mango in early August, I saw that as the woman in Virginia had predicted, bone had met bone, and while he’ll never have a fully functioning limb, the break had healed enough to allow him to put weight on that leg. In fact, when he’s standing still, you’d be none the wiser about the injury at all. Only when he begins to move does the slight limp give him away.

More than a year has passed now since Mango and Gimpy first appeared, and rarely a week goes by when they don’t visit. But I’ve never grown used to it. I hope I never do. I hope that in the months and years to come, each and every visit still fills me with the same sense of humility, wonder, and privilege that I feel now.

All too often we are reminded of the separation between our own human world and the natural world, reminded that these two worlds should not and cannot intersect without negative repercussions for one side or the other. Indeed, for most people, the closest interaction they’ll have with a deer is if they have the misfortune of hitting one with their car. It’s why I’ll never take for granted moments like the one I was witness to this past July when I lay on my tummy on the floor for fifteen or twenty minutes, hardly daring to breathe for fear of interrupting the scene that was playing out before me: Mango licking Gimpy’s injured leg as he nuzzled her back. A mother caring for her baby, the most natural thing in the world, and a reminder that for all our differences, we’re actually not all that different.

Perhaps that’s the draw for me. Why wouldn’t I chance a relationship with these creatures who live lives not unlike ours, but better? Innocent and pure lives free from the weight of worry and stress; lives that revolve around eating, resting, and nurturing relationships with those most dear to them. Lives in which decisions are driven purely by instinct and trust. How lucky am I to be invited into this exemplary way of being, if only for a few moments at a time?

And when it comes down to it, that’s why I keep the windows open and brave the autumn chill: to hear the crunch of forest floor under hoof—my cue to slow down, to ready myself for another foray into this realm that exists only at the point at which our two worlds overlap, for a few moments of perfect cohesion and beauty.

I step out onto the balcony and cross to the railings; on the other side the shy doe with the nick in her right ear and the baby with the bad leg are waiting. I drop to my knees and stretch my arm through the railings, apple slice in hand. And while neither mammy or baby hesitates, their large, brown and innocent eyes remain locked on me as they move forward. Then, going against everything their instincts tell them, they take the treat from my hand, sometimes even allowing my hand to rest for a few moments on their heads.

And that’s when I’m in it—that perfect place that exists only at the midpoint between our two worlds and only for as long as the deer are willing to extend to me their trust. It’s quiet there, the only sounds coming from the mouths of the deer as they munch their apples and carrots. And it’s still. It has to be. The deer are skittish, likely to bolt at any sudden or unfamiliar noise or movement, shattering the perfection of these moments. No matter how busy my day has been, or how much I’ve been running around, when I arrive at this place where our two worlds come together, I’m forced to slow down, and to stop. If these creatures can overcome their inherent fear of humans enough to grant me these few special moments, it’s the least I can do to respect and embrace the rules of conduct in their most simple, innocent, and uncomplicated of worlds.

But that’s just my view from the inside. On the outside, at that cross section where nature and civilization collide, look up on the hillside and what you’ll see is nothing more exceptional than a 29-year-old woman, down on bended knee, offering an apple in her outstretched hand, to a baby deer with a gimpy leg who willingly accepts.

Find Maura on Twitter at @maurawrites, and read more of her writing on her blog.

Illustrator Claudia Campazzo was born and raised in Chile and is also a classically trained violist and violinist. You can find more of her lovely work on her blog.

Yoga and Vegetarianism

I've been going to Back Bay Yoga almost every day since I moved to Boston at the beginning of April, and I've found the studio to be a very safe and friendly place in which to develop my yoga practice in earnest. I adore nearly all of their teachers, and have learned and evolved through pretty much every single class I've taken there.Recently my three-month unlimited membership ran out, and when they posted a new weekday morning line-up that didn't suit my schedule as well as the old one, I decided it was time to explore other yoga studios in Boston. I suppose I've gotten a bit too comfortable at Back Bay—I'll always drop in for classes on a weekly or near-weekly basis, and I may very well renew my unlimited membership at some point, but for right now I feel a strong nudge toward exploring new styles and learning with new teachers.

This is how I found myself this past weekend on the South Boston Yoga website. I'd heard they offer aerial yoga classes, which I was really excited to try. Imagine my dismay, however, when I spotted a paleo diet workshop announcement with a certified nutritionist!

There didn't appear to be any upcoming workshop on veganism to balance things out. More to the point, though, practicing yoga while eating animals is a contradiction, and once again I'll draw upon Rynn Berry's wonderful Food for the Gods to explain why:

Cobra, lion pose, pranayama and mudras. Anyone familiar with these terms for some of the physical and psychological techniques of yoga has probably taken yoga classes, and most likely remembers the feeling of peace and well-being that followed them. In India, the Jains, Buddhists and Hindus practice yoga, which is a set of practical exercises for attaining samadhi, or spiritual transcendence. The eighth hallmark of the ahimsa-based "vegetarian" religions is that they have attached to them a set of physical and psychological techniques for achieving ecstasy.

Professor Berry goes on to note that in the Western tradition "there is no yoga—probably because in classical yoga, spiritual progress is predicated on eating a diet of plant-based foods."That said, the "power yoga" we practice in studios all over the Western world bears little resemblance to "classical" yoga. As Dean Radin explains in Supernormal: "...[Y]oga as it is known and practiced in the West today, as a quasi-spiritual athletic practice, can be traced not to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, but to an amalgam of traditional yoga poses combined with Swedish gymnastics and British Army calisthenics."In my experience, most Western yoga teachers merely skim the surface of yoga's spiritual roots, mentioning "the heart center" or the "third eye" without getting into what any of this stuff actually means—an understandable omission given that most students are there for the workout. I can't ever recall hearing the word ahimsa spoken in a yoga class, and yet it is the most fundamental tenet of classical yoga: refraining from causing harm to any sentient being. Following this principle, of course, necessitates a pure vegetarian diet.I politely asked about ahimsa on the South Boston Yoga Facebook page. The next morning, I found my comment had been removed. I tried again, and after what seemed like an odd reply—"Basically, we are not an exclusive community, diet being one of the life choices that we do not persecute. This discussion can happen over a private message if you like"—my second comment was removed as well. Whoever is doing the social media for SBY clearly felt defensive, and chose to frame my logical questions as the intolerant harping of a hardcore vegan (e.g., using the word "persecute") rather than responding to my concerns in an open and forthright manner. I guess they're afraid that discussing the issue in public might turn people off the paleo class, but if they were to offer a vegan workshop too, they wouldn't lose anybody at all! I'm very sad that the SBY social media person chose to handle the situation this way. But I'm not writing this post to complain. Actually, as I was editing this entry I discovered that the paleo workshop has disappeared from the South Boston Yoga event calendar!Still, the issue has been raised, and I'd like to see it through: I've noticed that people on the paleo diet often justify their dietary choices by saying "I'm doing what's right for my body," and as a very happy and healthy vegan, it goes without saying that I consider this attitude a cop-out. (For a sensible take on cravings, read this great post from VeggieGirl. "It’s interesting that this type of logic is used to explain cravings for things such as meat, eggs and cows’ milk," Dianne writes, "but not when what’s being craved is vodka, coffee or donuts.") Furthermore, we shouldn't follow someone's advice just because they have a string of letters after their name; many medical doctors, after all, refuse to acknowledge the connection between the consumption of animal protein and the skyrocketing rates of obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer in America.My real "beef" with saying "I'm doing what's right for my body" isn't about the meat eater in question, however, and I invite you to meditate on the following statement:

But I'm not writing this post to complain. Actually, as I was editing this entry I discovered that the paleo workshop has disappeared from the South Boston Yoga event calendar!Still, the issue has been raised, and I'd like to see it through: I've noticed that people on the paleo diet often justify their dietary choices by saying "I'm doing what's right for my body," and as a very happy and healthy vegan, it goes without saying that I consider this attitude a cop-out. (For a sensible take on cravings, read this great post from VeggieGirl. "It’s interesting that this type of logic is used to explain cravings for things such as meat, eggs and cows’ milk," Dianne writes, "but not when what’s being craved is vodka, coffee or donuts.") Furthermore, we shouldn't follow someone's advice just because they have a string of letters after their name; many medical doctors, after all, refuse to acknowledge the connection between the consumption of animal protein and the skyrocketing rates of obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer in America.My real "beef" with saying "I'm doing what's right for my body" isn't about the meat eater in question, however, and I invite you to meditate on the following statement:

If a choice is truly right for you, it won't be wrong for anyone else.

Even if you don't believe that a cow or pig or chicken counts as "someone" (and you know I do!), what of the human animals who must go to work every day to slaughter, process, and package their flesh? Consider this passage from Gristle: From Factory Farms to Food Safety (Thinking Twice About the Meat We Eat), edited by Moby and Miyun Park:

Insane, right? And this passage doesn't even touch on the psycho-spiritual effects of working in a slaughterhouse (whether it's a factory farm or someplace "local" and "family owned"). If conditions are this heinous for the humans, imagine how much more horrific it is for the cows on the conveyor belt. This is why we practice ahimsa.

* * *

Sunday evening I went to a Jivamukti class with Nina Hayes (a fellow MSVA grad!) at Sadhana Yoga. Vegetarianism is one of Jivamukti's five core principles (video explanation by co-founder Sharon Gannon here; I'm also looking forward to reading her book on the subject), and at the beginning and end of class the teacher generally leads the class in a Sanskrit chant: Lokah samastah sukhino bhavantu. In English: May all beings everywhere be happy and free.Every time these words come out of my mouth, a lovely feeling of peace and centeredness settles over me, and the feeling was even more powerful given my frustrating experience over Facebook that morning. Nina also read this poem by Hafiz:

Admit something:Everyone you see, you say to them, “Love me.”Of course you do not do this out loud, otherwiseSomeone would call the cops.Still, though, think about this, this great pull in us to connect.Why not become the one who lives with aFull moon in each eye that is always saying,With that sweet moon language, what every other eye inThis world is dying to hear?

It all comes down to love, doesn't it? "Yoga" means "union" in Sanskrit, and to feel and spread and be love is to honor the interconnectedness of all living things. Nina says, "The teachings of yoga are clear in that if we want something in our lives, then we must be willing to provide it to others first. If we want to cultivate deep internal peace, freedom and love through yoga, our diet must reflect this."What do you think about the connection between yoga and vegetarianism? Is it fair to suggest that Western yoga should retain the classical yogic principle of ahimsa, or is the new power yoga "a different animal" altogether? Whatever your current diet, I'd love for you to share your perspective in the comments.And finally, I'd like to give a shout-out to South Boston Yoga for ultimately taking my concerns seriously—I really appreciate that. I feel like I can go for that aerial yoga class after all!

The "Happy Meat" Myth

I have often heard the word "humane" used in relation to meat, dairy, eggs, and other products like cosmetics. I have always found this curious, because my understanding is that humane means to act with kindness, tenderness, and mercy. I can tell you as a former animal farmer that while it may be true that you can treat a farm animal kindly and show tenderness toward them, mercy is a different matter.

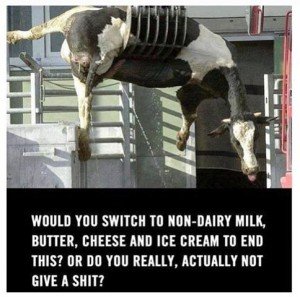

A few weeks ago I reposted this photo and caption from my friend Stephanie's Facebook page. Someone (whom I quietly unfriended) commented, "So that's how he jumped over the moon." (What upset me most about that comment wasn't its callousness, but the fact that this person is a parent, and will therefore be passing this attitude along to his child; and his child deserves better than that.)There is heinous cruelty perpetrated upon animals in factory farms all over this country, and unless you are a jerk (see above) it is more difficult to deny this fact once you've seen such an image. A couple of friends left more respectful comments, saying they purchase their dairy products from a local farmer. I know they mean well, and I'm glad they don't support factory farming any more than I do, but there is a lot of wishful thinking involved here. We like to believe that "happy cows" and "happy pigs" and "happy chickens" actually exist at those smaller farms, and while they may escape the most horrible forms of abuse like what the cow in the photo went through, they are still not treated as the pets or friends-on-four-legs the dairy and meat industry marketing campaigns would have you believe them to be.I am the first person to admit that before I went vegan I poured ordinary cow's milk (i.e., from a factory farm) on my Cheerios without giving a thought to the way those cows had been treated. I wanted to ask those Facebook friends, "How many times have you actually eaten hamburgers, steak, or bacon without knowing for certain that it came from an organic family farm, where the animals are treated 'humanely'? Never? Are you really that perfect?" Nobody is. Perhaps my definition of "humane" differs from the dictionary's, but as you know, I believe in the power of semantics. The use of the word humane, to me, begs a simple question: would I, as a human, want to be treated this way?

- I wouldn't want to live in a crate, cage, or stall, standing up to my ankles in my own feces.

- I wouldn't want my eggs or breastmilk taken from me on a daily basis. (My eggs! Crazy, right? We do tend to forget we have essentially the same reproductive equipment as the animals we eat.)

- I wouldn't want my child taken from me, destined to be somebody's dinner.

Am I just anthropomorphizing again? Do animals really have feelings of their own? Let's reframe. What would you do if you found yourself in a slaughterhouse queue? Is it safe to say you'd do absolutely anything to save your own life? So did this cow (and he's not the only one).When I was a child, I was lied to about how and why cows produce milk. I was told that cows "gave" milk every day as a matter of nature, and that farmers were doing them a favor by relieving their udders--that it was a "win-win" situation. No one told me that cows had to be forcibly impregnated before they could produce milk, just as my mother had to carry me in her womb before she could breastfeed me.Ultimately this "happy cow" stuff comes down to marketing versus honesty. If you want to eat animal products, that is, of course, your choice. But don't deceive yourself. Those cows, pigs, and chickens aren't remotely happy so long as we are exploiting their bodies for food.

God, grant me the courage to know what happens to animals, and the grace not to hate humans because of it.-- Victoria Moran (@Victoria_Moran) July 10, 2013

Is there Happy Meat? "The Ultimate Betrayal" lifts the veil of secrecy surrounding animal farming http://t.co/QKt48aqqyF #FactoryFarms #Book— VNN (@VeganNewsNet) August 22, 2013

What is "extreme"?

Once upon a time, if I ever heard someone call veganism "drastic" or "extreme," I wouldn't have disagreed. Back then, going without cheese did seem too difficult to consider as a viable lifestyle option.

ex·treme[ik-streem] ex·trem·er, ex·trem·estnoun, adjective1. of a character or kind farthest removed from the ordinary or average: extreme measures.2. utmost or exceedingly great in degree: extreme joy.3. farthest from the center or middle; outermost; endmost: the extreme limits of a town.4. farthest, utmost, or very far in any direction: an object at the extreme point of vision.5. exceeding the bounds of moderation: extreme fashions.

Today I believe we often use words like "drastic" and "extreme" to label things we just don't feel brave enough to contemplate. We forget that the unknown, by definition, contains just as many possibilities for "extreme joy" as big bad scary things—and that "the big bad scary things" might only be a matter of faulty labeling, too.So I'd like to offer some perspective—to reframe these words, if you will. Here is a short list of things I consider "extreme":1. Open heart surgery, or blitzing your body with toxic radiation.They saw your chest open, for crying out loud! The links between animal foods and disease are scientifically irrefutable. How is giving up cheeseburgers "extreme" in the face of such massive health consequences?2. Anal electrocution.Just so some clueless human can wear their fur? This is not just extreme—it is cruel and insane.3. Losing your beak, or losing your life before it's even started.At poultry farms it is standard practice to singe off the beaks of female chicks so they won't peck each other out of desperation in their hideously claustrophobic cages, and to throw "useless" boy chicks into a grinder—or leave them to die in a trash can. These are reasons why I will never eat another omelet as long as I live. (You'd like to think family-run farms don't engage in these inhumane practices, but you cannot be completely sure of this unless you are keeping your own chickens. Earlier this week I watched Vegucated for the first time, and it includes disturbing footage from a farm that bills itself as small, organic, family run, etc. They say they have to resort to such practices in order to compete with the larger factory farm operations.)Yes, these facts are horrible and disgusting. I absolutely wish that none of this stuff existed outside of nightmares. But if you find it disturbing, you are proving my point.

Compassion is Contagious™

My friend Stephanie has been doing a great deal of work recently with animals who are on their way to the slaughterhouse. Watching the videos, tweets, and posts coming out of amazing volunteer movements like Toronto Pig Save has reinforced for me that concern for animal welfare IS spirituality: this is what "the interconnectedness of all living things" actually means. Other humans will soon end their lives in a very violent way, and yet this sort of aid—a drink of water, a few loving words, a brief physical connection of hand and snout—can still make a world of difference to these sentient creatures.Toronto Pig Save put together the following short video to show you what they do. It's been a brutally hot summer, but I have a fan, a shower, access to drinking water whenever I need it, and my absolute freedom. These pigs don't enjoy any of those blessings.As I watched this video I kept thinking of the times in my life when I was thirsty. I tried to imagine that feeling magnified to this degree, but I couldn't do it. I couldn't imagine what it would be like to be confined like this, and in such unbearable heat.People sometimes say "you're just anthropomorphizing these animals," but I don't think so. You can see how desperate these pigs are for water—just as you or I would be. We humans don't have a monopoly on basic needs, or basic feelings.

What would happen if slaughterhouses had glass walls? @PaulMcCartney explains. WATCH & RT! VIDEO: http://t.co/Ozw5RdHhWe-- PETA (@peta) July 29, 2013

Of course, these activities are not limited to Toronto. In response to her Facebook and Twitter posts, Stephanie has been receiving inquiries and messages of support from all over the world, and she is helping to develop a broader organization called the Global SAVE Movement (Stop Animal Violence Everywhere). Here's a video she put up recently about setting up a SAVE group in your own community:On the surface, to focus on becoming a vessel of love and compassion might not seem all that "practical" or "effective." Yes, the animals are still going to die. But if you think back on the last time you were having a really shitty day and someone offered you a hug, a listening ear, and a heartfelt "I love you," you remember that these intangible gifts DO make a difference. (I love the Global Save Movement tagline, Compassion is Contagious™. For some downright hardwarming evidence that this is so, watch this "30 Days" episode in which a hardcore hunter goes to live with a family of vegan activists.)I'll end with a Youtube comment (on the first video) I found particularly cogent:

Global Animal Welfare Development Society

(Check out this interactive map to see where SAVE groups are popping up worldwide.)

Global SAVE Movement on Facebook

New York Pig Save on Facebook

Full Circle

With Tali and Margo on Washington Square East, en route to the PETA talk at the Kimmel Center. Photo by Rain.

As you may know, at NYU I was an opinion columnist for the Washington Square News. (If you're interested, here's the best thing I ever wrote for that paper.)One time the animal rights group on campus circulated a pamphlet stating that NYU researchers, funded by our tax dollars, were practicing vivisection on rhesus monkeys, supposedly to discover a cure for lazy eye. I was going to link to the definition of "vivisection," but I think I'd better define it for you here:

viv·i·sec·tion [viv-uh-sek-shuhn]noun1. the action of cutting into or dissecting a living body.2. the practice of subjecting living animals to cutting operations, especially in order to advance physiological and pathological knowledge.

I was so shocked and disgusted that I hastily typed up an opinion piece decrying what was going on in our university research labs. It was an absolutely lazy piece of so-called journalism--I did virtually no outside research--and the next day we published a letter from the NYU spokesman (part of whose job it was to take us pesky kids down a peg on a regular basis) that began, "Camille DeAngelis parroted the contents of a nasty pamphlet..."Funny that he should use the word "parrot," right? Because parrots repeat what's actually been said; they don't obfuscate, as humans are wont to do. The NYU spokesman didn't deny anything about the vivisection itself--he only attempted to rationalize it by saying people would be helped by the "work" they were doing, and that the animal rights activists were just getting in the way of medical progress. As if making use of our first-amendment right was "nasty," and drilling holes into monkeys' heads WASN'T.Yeah, I think the monkeys would have a thing or two to say about that. But we don't speak their language.

"A few polite words, properly placed, can change a life forever." --@IngridNewkirk at @PETA #vegan #govegan-- Camille DeAngelis (@comet_party) June 21, 2013

Does "progress" necessitate the torture of innocent, sentient beings? Scientists like T. Colin Campbell believe this to a certain extent--for without his lab rats we wouldn't have as much scientific evidence that a plant-based diet is THE way to fend off cancer, diabetes, and heart disease, and there's no denying that animal testing has saved many human lives through vaccines and other critical medicines. Our technology, however, has advanced to the point where animal testing (for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and so forth) is actually the least effective way of doing things. And yet many companies are still dropping chemicals in rabbits' eyes before sticking them back in their cages.I don't know about you, but I don't want to be a party to unnecessary suffering in any form. I wish I had actually joined People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals back at NYU, and gotten involved. I thought I was doing enough by being a vegetarian, but I know better now.

.@ingridnewkirk on speciesism: "We think we're sophisticated because we invented Cheetos and the dishwasher." @peta #vegan-- Camille DeAngelis (@comet_party) July 5, 2013

Ingrid Newkirk's lecture included photographs and video footage of animals doing extraordinary things...and animals being treated with extraordinary cruelty.As our vegan academy group walked down to Washington Square for the PETA lecture that Thursday night, I thought back on that ill-executed yet thoroughly righteous editorial I'd once written. I also remembered a brief conversation outside the NYU Main Building I'd had with a really nice girl named Lauren, who was active in the PETA group on campus and was thrilled that I'd written about the vivisection issue. I was sipping a hot chocolate, and I offered her some. She asked if there was milk in it, I said yes, and she politely declined.Why didn't I get it?I wasn't ready, I guess. But I really wish I could have been.

Ingrid Newkirk's lecture included photographs and video footage of animals doing extraordinary things...and animals being treated with extraordinary cruelty.As our vegan academy group walked down to Washington Square for the PETA lecture that Thursday night, I thought back on that ill-executed yet thoroughly righteous editorial I'd once written. I also remembered a brief conversation outside the NYU Main Building I'd had with a really nice girl named Lauren, who was active in the PETA group on campus and was thrilled that I'd written about the vivisection issue. I was sipping a hot chocolate, and I offered her some. She asked if there was milk in it, I said yes, and she politely declined.Why didn't I get it?I wasn't ready, I guess. But I really wish I could have been.

THIS is your milk, your cheese, your butter. Still think dairy doesn't hurt cows? http://t.co/sn0wG2g4px #Dehorning #Reasons2GoVegan-- PETA (@peta) June 21, 2013

(All Main Street Vegan Academy posts here.)